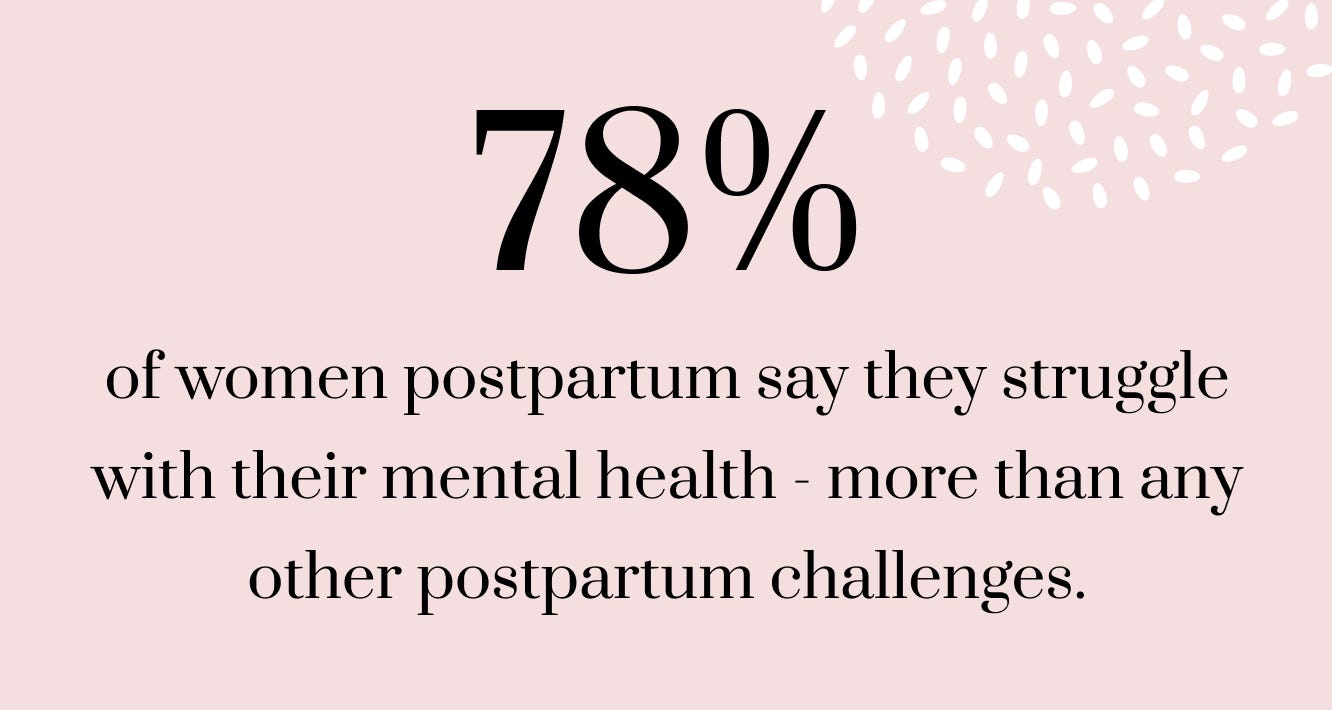

We know that the pregnancy and postpartum phases of motherhood can be challenging, but you are not alone.

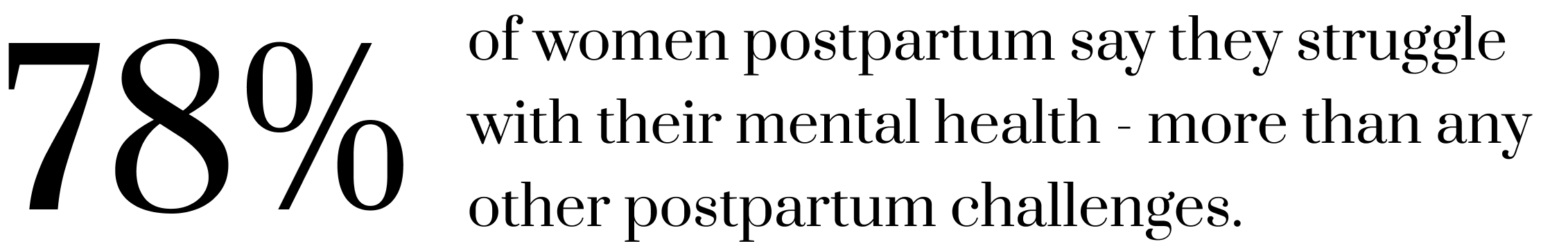

90%

of surveyed moms shared they experienced feelings of anxiety, sadness, stress or a low mood after giving birth.

50-75%

of postpartum moms are affected by the baby blues.

15%

Up to 15% of postpartum moms experience postpartum depression.

Ultimate Guide: Postpartum Depression, Anxiety, and Mental Disorders

It’s important to know the signs of postpartum depression and anxiety and how best to seek support.

We’re Here for You

We offer support groups, classes, and resources to help you navigate this complex journey. Reaching out for help is essential to help you and your baby thrive.

Classes

We offer live, online classes focused on your mental wellbeing, including our popular Brain-Boob Connection class. Whether you want mindfulness techniques to support your breastfeeding journey or how to establish healthy boundaries and a strong support network within your village when baby arrives, check your eligibility for our insurance-covered classes.

Community Support

Join thousands of other moms in our Facebook group: the Pumping Room. Moderated by certified lactation consultants, this is a safe space to ask questions and get answers from our team of experts or from other moms that have gone through the same experience.

Canopie

Aeroflow Breastpumps moms have access to the Canopie app, programs and coaching that support moms throughout pregnancy and postpartum.

Canopie helps moms with some of the topics they may struggle with most like sleep, feeding, relationships, identity changes, and more.

"Amazing: Aeroflow directed me towards this app and I am so thankful they did because I have used this app religiously during the first three months postpartum. I am pretty sure it saved me especially during my most vulnerable moments as a mom that has suffered from postpartum anxiety and depression massively with previous kids!" -Linah

Additional Resources

Whether you’re in your first month of pregnancy or preparing to wean from breastfeeding, we’re here to support your motherhood journey with insurance-covered classes and free resources

We’re here to support you and let you know that you are not alone.

OUR MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

The Brain-Boob Connection

This live, online class explains how your mental health can affect your breastfeeding goals and outcomes. Learn mindfulness techniques for feeding and pumping and practice breathing exercises to calm your body and mind.

The Canopie App

Aeroflow moms can access the Canopie app, including a customized-to-you audio & video program. There’s even more content to explore on the app, including live classes with experts and other moms.

Get to know Canopie

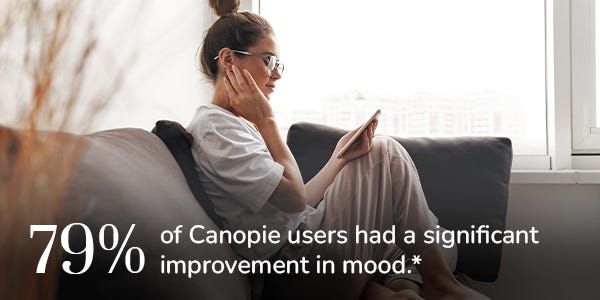

79% of Canopie users had a significant improvement in mood.

Reaching out early for resources can improve your breastfeeding experience and overall mental health.

Your mental health can affect your breastfeeding goals and outcome.

Co-created with moms and parents.

We've worked with over 200 mothers and 50 experts to design our programs. While our approach uses science-based methods, we know research alone isn't the answer. We were designed by and with moms to bring love, warmth, and connection to every session.

You are not alone.

Hear from other moms and parents through online recordings. You’ll have the opportunity to connect with other parents through pre-recorded audio sessions and live, community Q&As.

Feel better for your baby and yourself.

Canopie's program focuses on the challenges that all moms and parents face as they transition from the prenatal to the postnatal period. The takeaways include tactical practices for the now and strategies to implement long-term as well.

Being a great parent can mean asking for help.

Learn more about how the Canopie app works and how you can get started today.

Our Research

Results from our initial randomized controlled trial indicate significant clinical improvement after only 2 weeks of engagement.

reported a positive change in emotional health.

of participants with possible symptoms of depression had a clinically significant change in their mood.

said they would refer a friend to the program.

The research shows that long-term outcomes for moms and their babies are shaped by the wellbeing of the mom. Every expecting and new mother and family deserves to have the tools to help manage the inevitable ups and downs of this transition.